Up until now (except an attempt to rev a Rust pwn challenge that I immediately stopped), I’ve been reverse-engineering C compiled binaries. Until recently, I haven’t really been exposed to C++ compiled binaries.

In order to get a better understanding, it’s essential to understand the differences between C & C++.

C vs C++ comparison

C++ is an object-oriented language, building on top of C with additional features. Here’s a quick comparison:

| Feature | C | C++ |

|---|---|---|

| Data + Functions | Separate (structs + functions) | Combined (classes with methods) |

| Initialization | Manual or init functions | Constructors (automatic) |

| Cleanup | Manual free() calls | Destructors (automatic) |

this pointer | Passed explicitly as parameter | Hidden first parameter |

| Code organization | Procedural | Object-oriented |

C++ introduces constructors, destructors, methods, and objects. I won’t give a full course here because there are plenty of them online (such as “Learn C++ in 100 seconds!!!!” on YouTube).

Example Code

I made this simple C++ program, compiled it and then decompiled it. Let’s analyze it:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using namespace std;

class Person {

private:

string name;

int age;

public:

// Constructor

Person(string n, int a) {

name = n;

age = a;

}

// Method

void introduce() {

cout << "Hi, I'm " << name << " and I'm " << age << " years old." << endl;

}

};

int main() {

// Create two Person objects

Person p1("Alice", 20);

Person p2("Bob", 25);

p1.introduce();

p2.introduce();

return 0;

}

This program creates a class called Person, with a Person constructor and a method called introduce. We then create two objects, one is Alice and one is Bob. The constructor will initialize the object (Person p1), and the method will operate on that object (p1.introduce()).

Object-Oriented Fundamentals

Before diving into the assembly, let’s clarify some C++ fundamentals.

Constructor

A constructor is a special member function that initializes an object when it’s created. It:

- Has the same name as the class

- Has no return type

- Is called automatically when you create an object

- Turns raw memory into a valid object

Destructor

A destructor is a special member function that cleans up an object when it’s destroyed. It:

- Has the name

~ClassName - Has no parameters and no return type

- Is called automatically when an object goes out of scope

- Frees resources (like our internal

std::string)

Method (Member Function)

A method is a function that belongs to a class and operates on objects of that class. It:

- Has access to the object’s private data

- Receives a hidden

thispointer - Is called on a specific object (example:

p1.introduce())

The this Pointer

The this pointer is important to understanding C++ at the assembly level. It’s a hidden first parameter passed to every non-static member function that points to the object being operated on.

Why is it needed? When introduce() is called, it could be called on any Person object:

Person p1("Alice", 20);

Person p2("Bob", 25);

p1.introduce(); // Should print Alice, 20

p2.introduce(); // Should print Bob, 25

Both calls use the same introduce() function code, but they need to access different data. The this pointer tells the function which object’s data to use.

What we write:

void introduce() {

cout << name << age;

}

What actually happens:

void introduce(Person* this) {

cout << this->name << this->age;

}

The this pointer is passed in the rdi register on x86-64 Linux/macOS (System V ABI).

Decompiled Code Analysis

Let’s look at the decompiled code from Binary Ninja (I’ve kept only Alice’s introduction for now):

int32_t main(int32_t argc, char** argv, char** envp)

{

void var_59

void* var_20 = &var_59

void var_88

// create tmp string

std::string::string<std::allocator<char> >(&var_88, "Alice")

void var_b8 // allocate memory for object

Person::Person(&var_b8, &var_88) // pass to Person

std::string::~string(this: &var_88) // destroy the tmp string

Person::introduce()

Person::~Person()

return 0

}

Notes:

var_88: temporary string allocation for “Alice”var_b8: stack space reserved for the Person object

Why a Temporary String

We’re creating a temporary allocation for the string “Alice” in var_88. Why?

Because the Person constructor expects a std::string:

Person(string n, int a) // Expects std::string

But we’re passing a string literal:

Person p1("Alice", 20); // const char*

So the compiler creates a temporary std::string from “Alice”, passes it to the constructor, then destroys it.

The Object Allocation

We then create a memory allocation for the Person object in var_b8. This object will contain the data (member variables) for “Alice” and “20”.

If you look at this line:

Person::Person(&var_b8, &var_88)

It seems that we are passing the object to its own constructor, but that’s not exactly what’s happening. We’re passing the address of empty memory where the object will be built. The constructor’s job is to fill that memory with the proper values.

We can think of it like this:

var_b8is a location (address), not a Person object yet- The constructor receives that location

- The constructor writes data to that location

- After the constructor returns,

var_b8becomes a valid Person object

It’s time to pull out the disassembly to verify this. Let’s look at what’s really happening:

Calling Convention

Parameters to functions are passed in via the registers rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, and r9 in the System V ABI (used on Linux/macOS).

The return value is stored in the rax register (refer to https://wiki.osdev.org/System_V_ABI).

| Parameter | Register | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | rdi | this pointer |

| 2nd | rsi | string reference |

| 3rd | rdx (or edx for 32-bit) | age value |

| 4th | rcx | – |

| 5th | r8 | – |

| 6th | r9 | – |

| Return | rax | – |

So we have the object in rdi, the string in rsi and the age in edx (rdx).

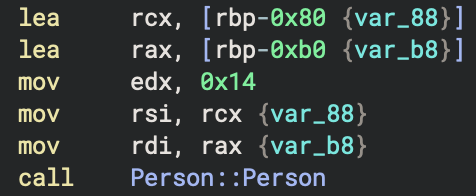

So for the Person constructor:

We are creating the string Alice, we are loading the object for Person in memory, and we are moving the age into edx.

Person::Person(

this = address of var_b8, // WHERE to construct => rdi (param 1)

name = "Alice", // WHAT to put in it => rsi (param 2)

age = 20 // WHAT to put in it => rdx (param 3)

)

IMPORTANT NOTE: This is the System V ABI used on Linux and macOS. If you’re reversing Windows binaries, the calling convention is different.

The introduce() Method

Calling the Methods

p1.introduce();

p2.introduce();

Diving into ASM:

; p1.introduce()

lea rax, [rbp-0xb0 {var_b8}] ; Address of p1

mov rdi, rax ; this = p1

call Person::introduce ; Call method

; p2.introduce()

lea rax, [rbp-0xe0 {var_e8}] ; Address of p2

mov rdi, rax ; this = p2

call Person::introduce ; Call method

The only difference between the two calls is which address gets loaded into rdi (the this pointer):

p1.introduce()→this = rbp-0xb0p2.introduce()→this = rbp-0xe0

Same function code, different this pointer, different data.

Object Memory Layout

Let’s look at the Person class to understand how objects are laid out in memory:

class Person {

private:

string name; // First field

int age; // Second field

};

Why These Sizes

std::string: 32 bytes (0x20) on most 64-bit systems- Contains a pointer to heap data

- Stores length and capacity

- May have a small buffer for short string optimization

int: 4 bytes- Padding: 4 bytes added for alignment (optional, depends on what follows)

Field Offsets

The compiler lays out fields sequentially:

namestarts at offset0x00(first field always at offset 0)agestarts at offset0x00 + 0x20=0x20(after the name field)

In C++, the first member of a class is always at offset 0. This is guaranteed by the standard.

A pointer to a structure object, suitably converted, points to its initial member. – C99 standard section 6.7.2.1 bullet point 13

If we move on to the introduce method of the Person() class, we are greeted with a rather brain-f*ck C++ decompilation:

Now let’s look at the orignal introduce() code:

void introduce() {

cout << "Hi, I'm " << name << " and I'm " << age << " years old." << endl;

}

It turns out that each << is an operator which is actually a function call.

The decompiler is showing every single function call involved in that one cout statement.

Operator Overloading

We also notice these are nested calls with different stream operator “types”. They’re called overloaded operators, and it basically means we can have multiple versions of the same operator (<<) that work with different data types.

For example:

ostream& operator<<(ostream&, const char*); // For string literals

ostream& operator<<(ostream&, const string&); // For std::string

ostream& operator<<(ostream&, int); // For integers

ostream& operator<<(ostream&, double); // For doubles

// ... and many more

So each type needs its own implementation, which is why we have:

std::operator<<<std::char_traits<char> >(for strings)std::ostream::operator<<(for integers)

The single line:

void introduce() {

cout << "Hi, I'm " << name << " and I'm " << age << " years old." << endl;

}

Becomes six separate function calls:

cout << "Hi, I'm "- Result <<

name - Result <<

" and I'm " - Result <<

age - Result <<

" years old." - Result <<

endl

Each call returns a reference to cout, which is then used as the first parameter for the next call. This way, we can keep chaining our prints to cout (method chaining).

How name is retrieved

mov rax, qword [rbp-0x8] ; Load 'this' pointer

mov rsi, rax ; Pass 'this' as name address

mov rdi, rdx ; Pass cout reference

call std::operator<< ; Call operator<<(cout, name)

We load the address of the Person object with no offset. This is actually passing the address of the name field, because in our object, name is at offset 0 (refer to object memory layout).

We know this because the first field of our Person class is name:

class Person {

private:

string name; // At offset 0x00

int age; // At offset 0x20

};

Since name is the first field, its address is the same as the object’s address (this).

How age is retrieved

mov rax, qword [rbp-0x8] ; Load 'this' pointer

mov eax, dword [rax+0x20] ; Load age VALUE from this+0x20

mov esi, eax ; Pass age value

mov rdi, rdx ; Pass cout reference

call std::ostream::operator<< ; Call operator<<(cout, age)

Our age field is at offset 0x20 (32 bytes) because std::string is 0x20 bytes large (on most 64-bit systems). We can then use type sizes to deduce layout of member variables (fields) in a class.

Reverse Engineering Patterns

Pattern Recognition

If you see the same offset used multiple times across different functions, that’s a field!

Here’s a cheat sheet of common patterns:

| Pattern | Meaning |

|---|---|

mov rdi, rax (no offset) | Accessing first field (offset 0) |

mov eax, [rdi+0x20] | Accessing field at offset 0x20 |

| Repeated offset across methods | Same member variable |

| String of function calls | Operator overloading (like <<) |

lea rax, [rbp-N] then mov rdi, rax | Passing object address as this |

Identifying Objects

When you see code like this:

lea rax, [rbp-0x80]

mov rdi, rax

call SomeClass::SomeMethod

You can deduce:

rbp-0x80is likely an object of type SomeClassrdireceives thethispointer- The method will access fields at various offsets from

this

Leave a comment